Assembling a battery pack for an electric racing car is all fun and games until cells start to spark, bolts start falling out, and you end up questioning your competence as an engineer!

I had the opportunity to lead the assembly process from individual cells to a functioning battery pack powering a North American record-breaking vehicle. Although I learned a lot, it did not come without the hours of struggle and the banter with my team that comes when you are close to the tipping point.

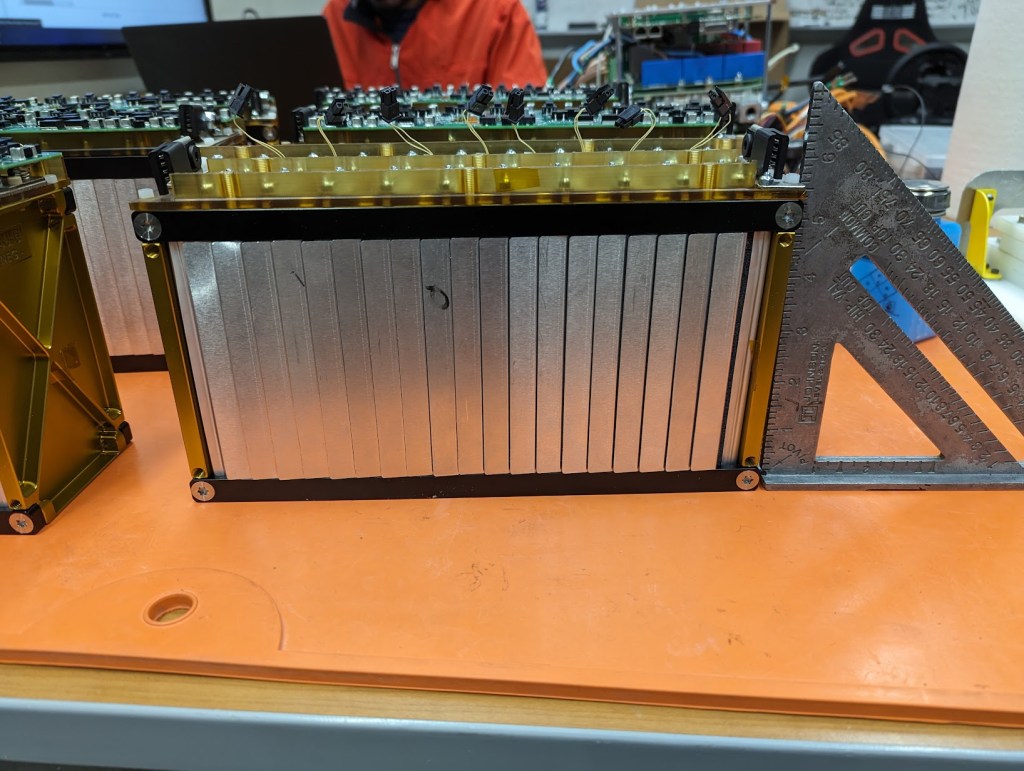

To give some more context, think of the segment like a sandwich, where the golden end plates are slices of bread, a Lithium-ion pouch cell stacked with a foam stuck on a thin aluminum sheet repeats twenty-one times to make up the filling. This sandwich is then compressed, and the black beams are added to ensure the filling does not fall out and the end plate stays in position.

Image credits: Designed and rendered by Electric drives team at HyTech Racing

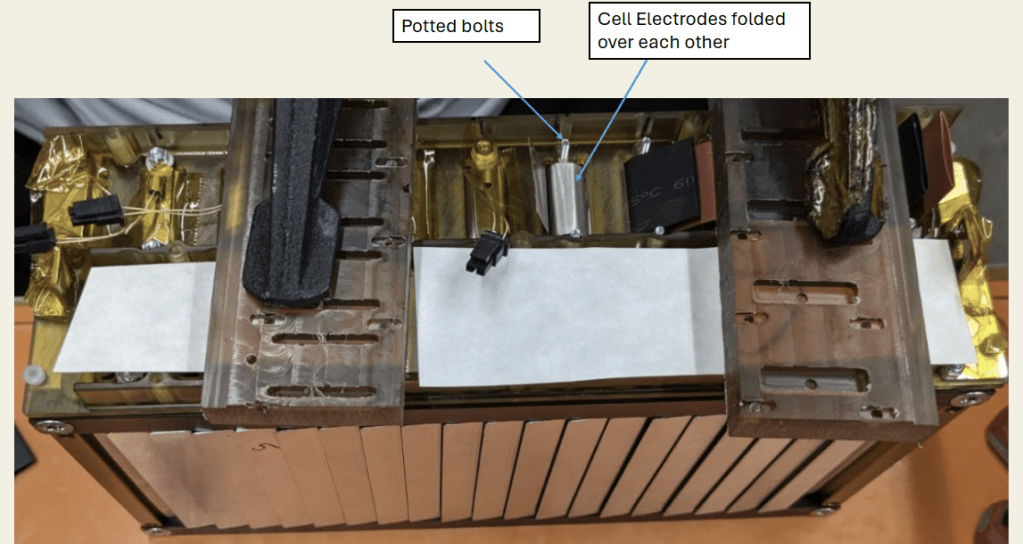

Each pouch cell has two electrodes sticking out and the cells are connected in series by folding tabs of two adjacent cells over each other and bolting a bracket to make the connection. These connections are arranged on the transparent yellow structure on the top of the segment and the BMS (green board) is mounted atop the plate.

There are multiple tedious steps and checks to complete the assembly. Only when you must redo these steps for the fifth time for the first out of six segments do you realize the importance of doing it right the first time. An ideal segment takes around 3 hours from start to finish; it took a team of four two weeks! The errors usually cascaded and every time we made a mistake it increased the chance of failure in a different step of the process.

Our initial problems started with misalignment. We relied too heavily on the compliance of the foam sandwiched between the cells to overcome issues caused by tolerance stack-ups and improper positioning. Once we had solved that issue it seemed like we had a clear path to victory. But knowing our luck as a team we should have known better!

Once we had spent hours realigning the cells the mistake that followed was a well-known disaster. It is the type of error that comes when your attention starts to dwindle and the engineering gods decide to wake you up.

I was in the process of completing the cell connections and a bolt slipped through my fingers. For a split second, it contacted two electrode tabs causing a bright flash and a sharp bang, instantly biting out half the electrode. I had shorted my first cell which at this point was an annual tradition of our team. Sadly, this happened three more times over the entire assembly process. For both of these errors, we had to redo all the bolted connections, which brought another failure mode that no one anticipated.

To add some more context to this last type of failure: the transparent plastic plate had bolts potted into it and they were used for attaching the brackets that clamped the electrodes together. After 30 minutes of turning a ratchet driver, I was finally onto the last lock nut. I carefully placed the nut over the bolt and as I gently turned my ratchet driver I felt something was off. Just as I pulled the socket out I realized to my absolute horror that the bolt had backed out.

After spending some time thinking about a way to avoid reassembly I found myself starting the disassembling process. It took us another day to identify the reason behind the failure: the bolt heads rotated slightly every time they were tightened and loosened, which cracked the adhesion with the plastic. This meant that we had to repot all the bolts and go back a few steps.

There were many times when it felt like we were one mistake away from complete disaster, after all each battery segment had a potential difference of 80V which was considered High Voltage and dangerous. The working environment was far from perfect and each mistake was costly in terms of time and resources. Despite our setbacks, we rarely complained and just powered through the tedious process!

Lessons

Learning through experience is much more potent than any form of study technique. It is extremely easy to read about DFA, solve problems about tolerance stack-ups in exams, and even convincingly discuss these topics in interviews. Yet, one only understands the significance of good engineering decisions until it is 3 am and you have been trying to align the holes between two parts and the bolt just does not want to go in!

As silly as it sounds, I believe that maintaining your sense of humor during these projects is ultimately what makes the most tedious of tasks enjoyable. While it might lower your productivity, the overall process ends up being more memorable and you end up with a higher tolerance for sufferring.

When dealing with a challenging deadline, the sheer will of a young team usually makes up for lack of knowledge and experience. Our team usually just threw ourselves into the heat of the problem hoping to solve it, and for the most part that worked. But occasionally the “move fast and break things” method actually breaks something valuable and you realize that spending time thinking about a problem might have been a better investment of your time than fixing a rushed iteration.

I don’t know why the ability to take risks and be so bold diminishes with age and how we can prevent that from happening, but that is a rabbit hole for another time. I find it fascinating how engineering is filled with tradeoffs and it is ironic that a field so driven by data does not have a universal blueprint for solving problems. I suppose, that is what makes building new things so exciting!