In the race of the replicators [1], where success is measured by the speed of evolution, memes have recently outpaced genes. For most of history, the gene was the only replicator in the race until we arrived. It took us a while to warm up, but after we learned how to think in symbols, our ideas evolved much faster than the bodies they were created by. It is said that “revolutionary change is brought by evolutionary processes”; however, evolutionary change itself happens in bursts. I am trying to improve my understanding of how new things are created, and what follows is an attempt to get more insight into some flavor of the question: how does innovation happen?

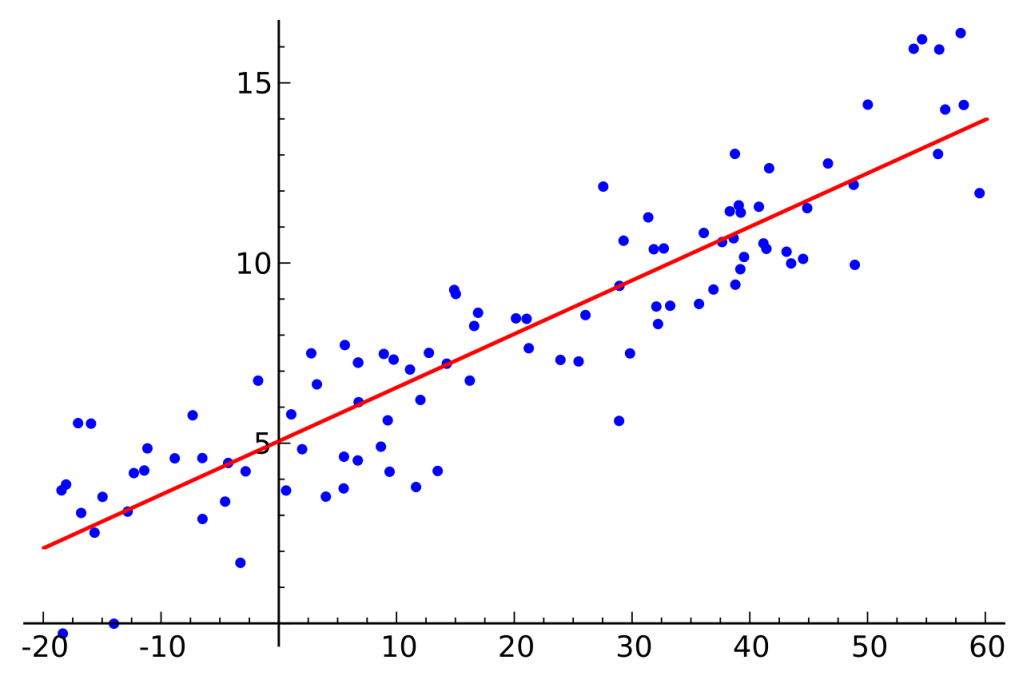

A single true narrative to answer the question would be convenient, but our incomplete and biased history needs to be analysed with various lenses. This is similar to how state estimation is done in Robotics, where multiple sensor measurements (that are individually noisy) are combined to collectively provide a better estimate of a robot’s state. There are many good explanations to the innovation question but there is no universal blueprint for creating things that transform the world and that is puzzling.

One approach would be to trace our answer back to true first principles. After all, the laws of physics are our most powerful explanatory tool that give us our best models of reality. However, if we started from atomic interactions and tried to explain how ChatGPT came about, it would be impossibly tedious, like navigating the Earth with a 1:1 scale map.

Alternatively, the power law or some version of the Great Man Theory can be applied to get a more zoomed-out version of history from which we can pinpoint the root causes of modern advances to specific moments and individuals. These make for glorious stories that are easy to understand and thus spread rapidly, but I think they sacrifice too much nuance. For example, Steve Jobs had an enormous impact on Apple’s success, but at the same time, it is obvious that Steve Jobs was not in the trenches of Shenzhen putting your iPhone together. Forget smartphones, no individual knows how to make a widget as deceptively simple as a pencil from start to finish, yet the world produces 55 million pencils per day!

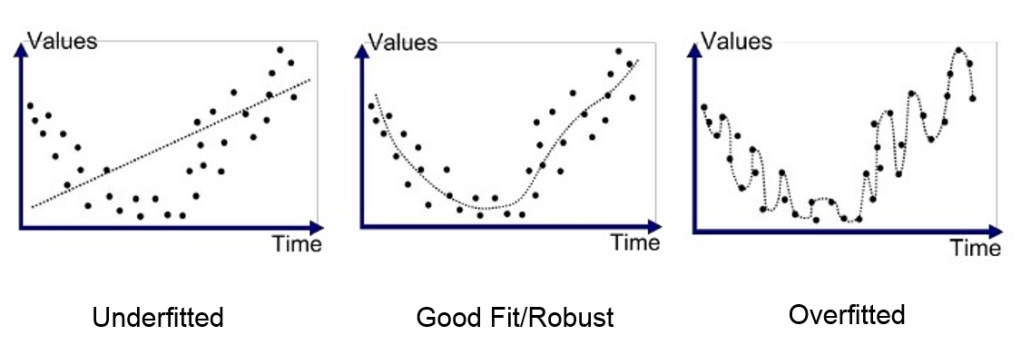

And so there are two extremes: the overly complex causality chain that results from a bottom-up explanation, and the overly simplistic story of the great innovator that bends the world according to their will. A simple workaround would be to say that the answer is somewhere in the middle, and the book How We Got to Now by Steven Johnson expresses one such solution: “History happens on the level of atoms, the level of planetary climate change, and all the levels in between. If we are trying to get the story right, we need an interpretative approach that can do justice to all those different levels”. I will now explain this approach of answering the “how innovation works” question.

The random mutation to natural selection pipeline has been the default method of innovation on our planet, and the following is one story that illustrates its unexpected achievements. Flowering plants replicate via pollen transfer, and insects enjoy energy-dense food. Flowers gradually produce nectar along with features like scent and colors to advertise the sweet nectar’s presence to insects. Concurrently, insects improve their ability to sense and extract nectar from different flowers, and in this process, they help transfer pollen. In this mutually beneficial trade, there is one critical action that insects need to perform for nectar extraction: hovering.

A honeybee hovers by flapping its inertially friendly wings over 200 times a second. It can sustain this without obliterating its nervous system because a single neural signal triggers multiple contractions of its muscles, which are mounted on an exoskeleton (a stiff spring) that can absorb these contractions. Most birds cannot enjoy the sweet nectar of a sunflower because their heavier wings flap too slowly for them to stay in one place. However, a hummingbird, which is lighter than most birds and heavier than most insects, finds a way. Its wings, which can flap at a frequency of 80 Hz, make a figure 8 pattern that generates lift both during the upstroke and downstroke (the majority of birds generate most lift on their downstroke). The stiffness of these wings, combined with powerful pecs that would make Arnold’s chest seem unimpressive, makes the hummingbird’s flight Super-Duper cool.

Before hummingbirds were around, a biologist studying pollinators could not have predicted that the insect-flower symbiosis would lead to a great innovation in the flight mechanics of birds. But with hindsight, there is clear enough mapping between these two developments. Johnson calls this the “Hummingbird effect” and uses it to explain how innovation unravels in human societies: building new technologies sparks changes that are unpredictable both in terms of their magnitude and the downstream network effects, but a tangible causality chain can be traced through history that links these different developments.

A key example that illustrates this in the book is the invention of the Gutenberg Printing Press. It’s obvious that the first-order effect was the improvement in literacy of the masses. But reading led to far-sightedness becoming a concrete problem in need of a fix. Spectacles solved this problem, but the wheel of innovation continued to spin, and we developed lenses that far exceeded the requirement of reading a book. Eventually, these lenses contributed to the invention of the microscope, which allowed us to see the world in more detail than ever. The printing press didn’t just make books cheaper; it fundamentally changed our perception of reality, both literally and metaphorically. Just like the hummingbird’s case, no one could have predicted that the printing press would lead to the invention of the microscope, but according to Johnson the causality chain between these events is far more plausible than some butterfly effect type explanation.

In writing this, I got a useful reminder about the difficulty of predicting the future. Genes innovated slowly, patiently sculpting life over billions of years, and they still brought about unpredictable changes. Memes are evolving rapidly, so you can imagine how hard it is to predict how human innovation unravels. It won’t be in a straight line. This tangled web of many connections will only turn into a legible map with hindsight.

Notes

Any explanation that requires historical evidence turns into a very gnarly problem that is comically beyond my scope. But it is fun thinking about these things sometimes.

I have not found a way (yet) to integrate the takeaways below, but I find them interesting enough to be left as tweet-style bullet points.

- Improving the ability to measure is huge – “a pendulum clock helped enable the factory towns of the industrial revolution”.

- Lone geniuses that are far ahead of their time do exist – Charles Babbage designing the first computer and Ada Lovelace writing the first programs in the 19th century – but these are rare.

- In most case studies of innovation, multiple people end up making similar discoveries at the same time. The Rick Rubinian way to phrase this would be to say that the time of an idea has arrived. This is more true in Science and Engineering than it is in art: someone else would have discovered general relativity, but no one else could have painted the Mona Lisa.

- However, there needs to be sufficient prerequisites for an idea to come to life. One cannot build high-power lasers before the discovery of artificial light bulbs.

- The concept of ideas mating with each other to produce new ones – as explained by Matt Ridley – is repeated in this book.

References

[1] Richard Dawkins’s definition of a replicator: any entity in the universe of which copies are made